Main Menu

| Home |

| News |

| Research |

| Coding |

| Teaching |

Articles

Introductory Introductory Quick Studies Quick Studies Reseach & Technology Reseach & Technology Technical Reports Technical Reports Operating Systems Operating Systems e-Society e-Society MethOdd MethOdd Diving Diving Miscellaneous Miscellaneous |

| Action |

| AboutMe |

| On-Site |

Related Articles

| Scientific blogging: Is it worth it? |

|

|

|

| Written by Harris Georgiou |

| Friday, 17 September 2010 00:00 |

|

There is a big difference between writing a research paper for a scientific publication or conference, an article for a magazine or a newspaper and a daily post for a personal blog or homepage. Each has its own set of rules, it own attributes and features, necessary for a well-put publication and a well-received reception by the intended readers. However, Web 2.0 technologies have enabled the merging of different types of publications into one, the Internet, with millions of authors and billions of readers. Science is not an exception. Countless articles are presented in the Web as “scientific” in content, but there is a thin line between solid science and speculation. Are personal blogs appropriate for such everyday-science content and, more importantly, can they be trusted as true? What is "scientific" blogging?Well, blogs are not meant to publish research papers. Everybody knows that. The reason is not because of the content or the medium; it’s because of the intended audience. Many respectable public repositories of scientific papers like arxiv.org and citeseer.net contain a vast amount of true scientific knowledge. Scientific publications like Nature, Scientific American and New Scientist have their own blogging sections. Dedicated portals like Science20.com and Scientceblog.com publish thousands of science-related posts daily. There are even Facebook-like social networks for scientists, like ResearchGate and Academia.com. There is a notorious “guide for authors” (pdf) for those who wish to actually publish a research paper in one of IEEE’s scientific journals. It illustrates, in a very graphic and hilarious way, the difference between a simple statement like “1+1=2” and the way it should be presented in a more impressive scientific form. The sad thing is, it’s not very far from the truth! Everyone who’s working on research and writes such papers has at least a few similar stories to tell, where a submitted paper was rejected in one journal as insufficient, only to get published in another with honors. Recently I came up to a related short post by Alex Smola in his blog, explaining why keep up a blog or a full site with almost entirely scientific posts. He says that, besides having fun with it, there are things about science that cannot be circulated in the “proper” way – either because the length or style is not acceptable for a real publication in a scientific journal, or because the idea is so simple and useful that it must be circulated in the proper way to people who do not have the academic background or the time to go through tons of equations and diagrams. What is the "proper" peer-review process?So where is the difference? How does a full research paper compares to a simple post in a “scientific” blog? Well, the simple answer is: peer-review. The long answer is that others, experts from the same scientific area are normally called to assess and evaluate the content of the new work, compare it to the current state-of-the-art in that particular field and make an informed recommendation to the editor of the publication, typically a journal or a conference organizing committee, whether it is worth to be published or not.

It s important to not that the anonymity and the no-fee policy for the reviewers remain integral parts of the peer-review process, as this guarantees no side-gains or incentive to do this for living. In other words, Every new work is submitted and presented to the whole academic community as-is, some of the scientists (typically two or three individuals) with proven expertise and credentials in the field, accept the assignment of carefully reviewing this work and provide an informed recommendation about its validity, quality and novelty. This is not a closed community – in fact neither the author or the reviewer knows about each other’s true identity. The editor of the journal or the organizing committee of the conference is responsible for the proper assignment of submitted papers to reviewers, avoiding of course any conflict of interest, like assigning the paper for review to a co-author or a colleague. Based on the principle of good will, academic excellence, anonymity and fusion of multiple recommendations, the process is considered both fair and reliable, in terms of scientific integrity and validity.

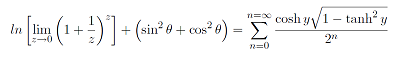

Advantages and fallbacks in the Web 2.0 eraThe new Web 2.0 technologies have made this process both easier and more “dangerous”. Papers are new submitted, distributed and evaluated 100% electronically, which means that anyone in the world may be considered as a valuable reviewer in his/hers area of expertise, by any journal of conference committee in the world. The “dangerous” news is that anyone can now self-publish his/her own work to the whole world via a homepage or a blogging site, completely outside the normal peer-review process. I can claim anything I want, even provide a few fancy equations to “prove” it. The thing is, everyone can now access and read my “scientifically proven” claims – but not everyone can actually evaluate the validity of my “proof” because not everyone has the necessary expertise and academic background to do it. So where does that leave us? Can real science be posted on blogs and web pages? Of course it can. No one can prevent it anyway, nor it should be. The question is not what gets published but how the average reader assesses its validity, its credibility as a source of knowledge. In formal scientific publications, the peer-review process establishes an acceptable level of credibility to the published works, as not everyone has the necessary expertise to correctly evaluate every single paper in every single research area. It’s never 100% certain, it never is in true science, but it’s generally “adequately close” to that. Do you think the “IEEE guide for authors” I states earlier is correct? Think again. The running variable z in the limit in the definition of e is incorrect, it should go to infinity instead of zero. If it was really a scientific paper and not a joke, this would be bad, really bad. In crowdsourcing, information is propagated and supported or declined by massive amount of readers, each with a limited level of expertise but with the option to give a “thumbs-up” or “thumbs-down” to this piece of information. In other words, the high-level expertise of two or three reviewers is substituted by many thousands of average readers. The question is, does this work equally well? There are three very important preconditions to this: 1Each reader’s opinion is statistically independent to each other, i.e., no one can influence the other’s recommendation on this, good or bad. 2Each reader’s expertise in this area of interest is at least of average level; if he/she has to select between “yes” or “no” on this, he/she should be able to judge correctly at least half of the times, i.e., better than random guessing. 3The mechanism for submitting and aggregating the readers’ recommendations must be reliable and tamper-proof. It doesn’t have to provide full anonymity, since even the author too can give a “thumbs-up” to his/her own work. But this single opinion will probably be lost (statistically) within the vast amount of “votes” from the other readers, provided that the author cannot mess with the ballots. When these preconditions hold true, the famous Condorcet jury theorem proves that, as the size of the pool of voters/readers increases, the aggregated outcome becomes more “correct” and reliable. What it really means in this context is this: If a large amount of readers know what the post is all about and provide their honest opinion about it, then the total outcome of “thumbs-up” and “thumbs-down” about it should be very close to the truth. ConclusionIs this enough for a blog to be self-acclaimed as “scientific”. Is that all it takes, a “thumbs” or ranking system for the readers to play with? Well, it could be. It’s that grey area (it’s always there!) between the full peer-review process of academic journals and the no-review process of a personal blog. It’s all a matter of being skeptical, informed and educated before making a judgement on what to call “scientific” and what not to, especially when it comes to sources on the Web. It’s not far from the truth the saying that: “…Digging out the truth from the Internet is like trying to drink some water from a fire-hose…”

|

| Last Updated on Thursday, 29 September 2011 22:37 |

Every scientific journal or conference has it’s own acceptance level and reputation among the academic community, mostly having to do with the quality and breakthrough content of the papers presented there throughout the years. Similarly, the standards for accepting a new paper for publication are as high as the quality of the previously published works there, usually measured by the total number of citations it gets every year. Although this “

Every scientific journal or conference has it’s own acceptance level and reputation among the academic community, mostly having to do with the quality and breakthrough content of the papers presented there throughout the years. Similarly, the standards for accepting a new paper for publication are as high as the quality of the previously published works there, usually measured by the total number of citations it gets every year. Although this “